Using images to tell a story is a common thread throughout human history. From cave drawings and fresco murals to comics and graphic novels, some things can’t be communicated through words alone.

Personally, reading and making comics has been an integral part of my life. Today I’d like to share why using comics in the art room can be powerful starting with their fascinating history.

A Bit of Comic Book History

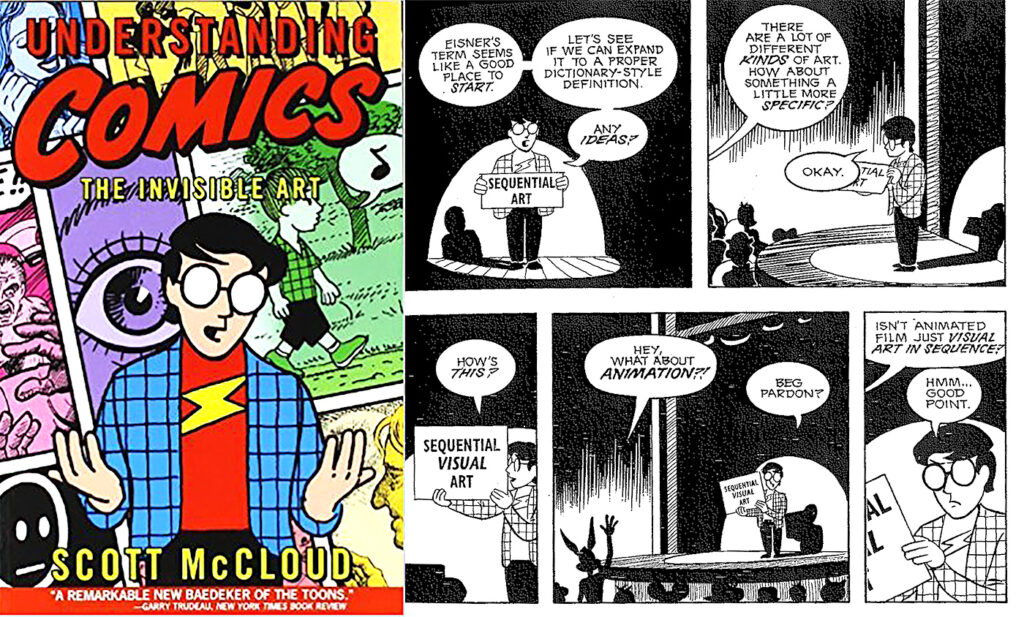

Images have been used to tell stories for centuries. In fact, we could consider almost all visual art as expressing narrative or ideas through images. So what sets comics apart? Scott McCloud does a great job of breaking down the concept of comics in his book Understanding Comics. He describes comics as “Sequential Art,” though he goes much further into detail in the book as seen in the excerpt below.

Comics emerged as a popular medium in the early part of the 20th century. The most prominent examples of the time featured westerns, sci-fi, and romance themes. Daily comic strips in newspapers also developed as an outlet for creativity and expression.

Bang! Pow! Zap! Superhero Comics

Of course, superhero comics were another popular genre. The history of these books is broken into four eras spanning from the 1930s to present day. The most recent era is known as “The Modern Age of Comic Books.” It started in the mid-1980s and features an explosion of characters, many of whom are darker and grittier with a stronger basis in reality.

The Comics Code

While comics have often been a flashpoint for controversy and social change, they hit somewhat of a roadblock in the 1950s. It was during this decade that Fredric Wertham, a psychiatrist, published Seduction of the Innocent. The book led a smear campaign of comic books, focused on what Wertham believed was the glorifying of violence and deviance within comics. For years, comics were heavily censored and regulated by the Comics Code, a system that prohibited depictions of drug use, violence, and sex.

But alternative comics, and eventually mainstream publishers, began to publish stories that tackled these significant topics. These were the types of stories young people were interested in and wanted to read.

Spiderman, Green Arrow, and other heroes began tackling drug abuse and crime and highlighted the ways individuals could make a difference. Race and sexuality also became less taboo, and heroes were challenged to fight against not only supervillains but broader societal issues, revealing nuances within their characters and identities.

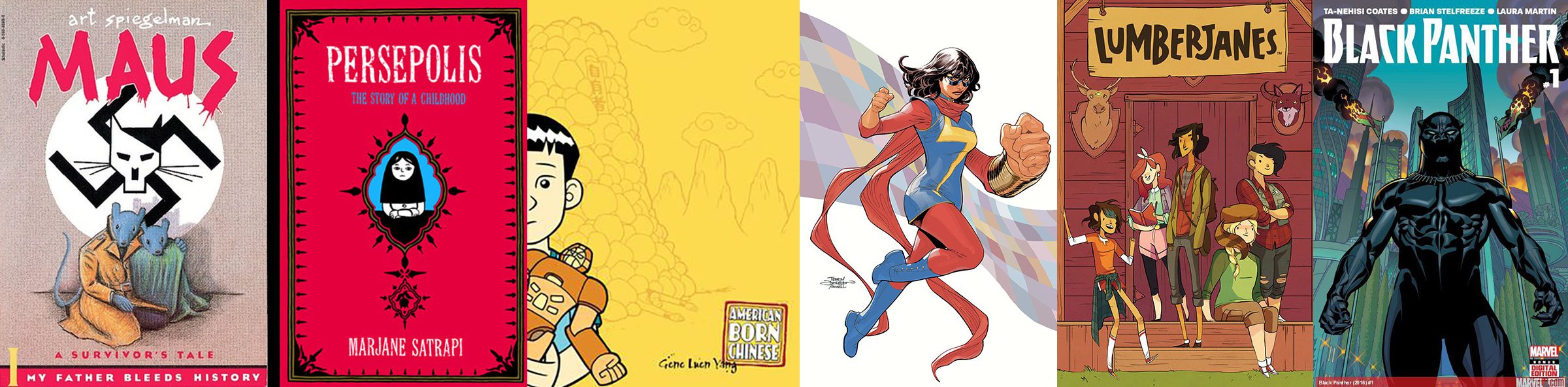

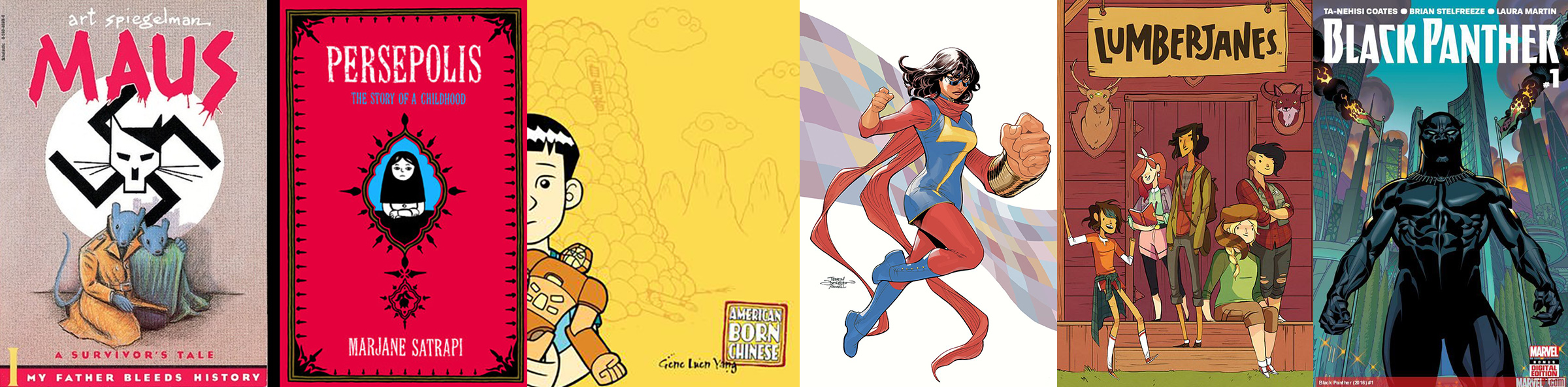

6 Modern Comics to Capture Student Interest

Comics today represent a wide swath of experiences and interests. They tackle issues of race, gender, and sexuality in a deeper and more meaningful way than in the past. Here are six comics to engage your students. Of course, you’ll want to make sure the content is appropriate for the age you teach.

1. Maus

This book, by Art Spiegelman, depicts the author interviewing his father about his experiences as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor. The graphic novel represents Jews as mice, Germans as cats, and Poles as pigs. Released in the 1990s, it became the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize (the Special Award in Letters).

2. Persepolis

Persepolis chronicles author Marjane Satrapi growing into adulthood in Iran during and after the Islamic Revolution. Groundbreaking for its depictions of a young girl’s life during conflict, it was originally published in French. It has since been translated into several languages including English.

3. American Born Chinese

Created by Gene Luen Yang, this story consists of three separate tales. The first is based upon the folk-tale of The Monkey King. The second is a story of a second-generation Chinese immigrant who lives in a mostly white California suburb. Finally, the last is a story of a white American boy named Danny, whose Chinese cousin Chin-Kee visits and embarrasses him. All three parts connect and create a narrative of assimilation, adolescence, and pride.

4. Ms. Marvel

This superhero comic book character was created by writer G. Willow Wilson and artist Adrian Alphona. Introduced in August 2013, she is Marvel’s first Muslim character to headline her own comic book and stars in her own solo series, Ms. Marvel.

5. Lumberjanes

This book is created by Shannon Watters, Grace Ellis, Brooklyn A. Allen, and Noelle Stevenson. It follows a group of girls who attend a summer scout camp and the strange creatures and supernatural phenomena they encounter there. It depicts strong female characters and explores gender roles and identity.

6. Black Panther

Created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Black Panther first appeared in 1966. Black Panther’s real name is T’Challa, and he is king and protector of the fictional African nation called Wakanda. Most recently, author Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote an award-winning run on the book, elevating the character’s status. In addition, the recent feature film has broken records and has given African American audiences representation in mainstream media.

2 Comic Projects to Try in Your Classroom

Now that you have some history and examples, how do you generate content to help inspire your students to tell their stories?

Project 1: Tell Me About You!

Coming up with ideas for stories is one of the toughest things for students. To get started, I like to refer students to the topic they’re most familiar with: themselves! A great first day or early-in-the-school-year project is a short intro comic. Provide students with a series of panels and have them fill in the spaces, based on a series of prompts. Download a blank sheet to use with students below!

My favorite prompts include:

- My Name is…

- I’m excited about…

- During winter/summer break I…

- Art is…

For students who aren’t comfortable drawing, you can incorporate photos into the project. Have them take pictures of themselves against a blank backdrop with a camera or iPad. Then, print them on regular paper in black and white. Students can draw with colored pencils on top of the photos to show themselves doing certain activities or being in different places.

Project 2: Creating Story Arcs

As you begin to get into more complex comics and plots, students might need a bit more guidance. Though they might complain, having them write down ideas and flesh out plots before drawing is an important part of the process.

The main structure of most comic book stories involves 3 acts:

- An introduction of context and characters.

- The conflict encountered or goals to be achieved.

- The resolution of the conflict.

Working with students to break their stories into these phases helps create a story arc.

As far as the drawing component, there are lots of great additional references that discuss visual storytelling and character creation.

Two of my favorites are:

- Comics and Sequential Art

Written by the legendary cartoonist Will Eisner, creator of the Spirit, this book analyzes the comics medium. It is based on Eisner’s teaching a course at New York’s School of Visual Arts. It discusses narrative storytelling by demonstrating principles and methods of the medium. - How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way

How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way is a book by Stan Lee and John Buscema. It serves as a primer for aspiring comic book artists and uses examples from Marvel Comics. It was first published in 1978 and has been reprinted regularly. It is considered a bible on comic book narrative and storytelling.

So get started with your comic books while giving your students a bit of history for the medium and the power that the combination of narratives and images can have!

What are your favorite comic book characters?

How do students create narratives in their work in your class?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.