Rubrics are serious business in the high-accountability culture of education. However, they often come across as dry and uninteresting, and language used in them can be vague and unclear. The goal of a rubric should be to provide a student with support and feedback about their work. But how many rubrics are actually student-friendly? Not enough!

Here are 4 tips to create crystal-clear rubrics that are easy for your students to understand and enjoyable for them to fill out.

1. Be clear when it comes to your learning objectives!

Understanding by Design, also known as backward design, is an extremely useful approach to developing rubrics and curriculum. Developed by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, the framework focuses on designing curriculum “backward” by starting with the ends or outcomes you hope to achieve.

Here’s how it works with rubric development.

- Start by identifying what you want students to know, understand, and do before developing the activities.

Are you trying to build an understanding of value scales with your students? Working on technical drawing skills? Clarity of objectives is key! - Decide what kind of performance spread you are assessing.

Predicting the range of student outcomes can help determine if the objectives are too broad or too narrow. For example, trying to assess the “quality” of photographs taken by a student might encompass too many factors as a single objective. However, breaking it up into 1) Clarity of subject, 2) Ability to properly focus, and 3) Composition of images is much easier to identify and assess. - List your specific objectives before coming up with the activities.

Often, teachers will come up with the idea for a project and then figure out how to assess it afterward. This can lead to a disconnect between the work and assessment. Working backward provides a clearer connection between the two.

Looking for even more information about assessment in the art room? Don’t miss the AOE Course Assessment in Art Education! You’ll leave the course with a comprehensive toolkit that has many different types of authentic assessments ready for direct application in your classroom!

2. Choose the appropriate assessment tool.

What exactly are you trying to measure? Knowing and understanding what and how you’d like to assess things is really important. This article by Karen Erickson, a theatre artist and educator, is a great primer on whether a rubric is even necessary for the task you’re assessing. According to Erickson:

A rubric is a tool that has a list of criteria, similar to a checklist, but also contains descriptors in a performance scale which inform the student what different levels of accomplishment look like.

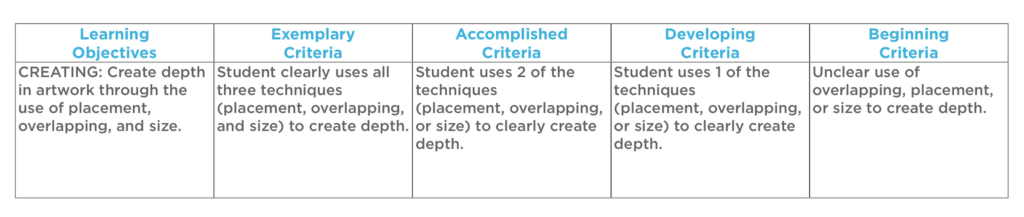

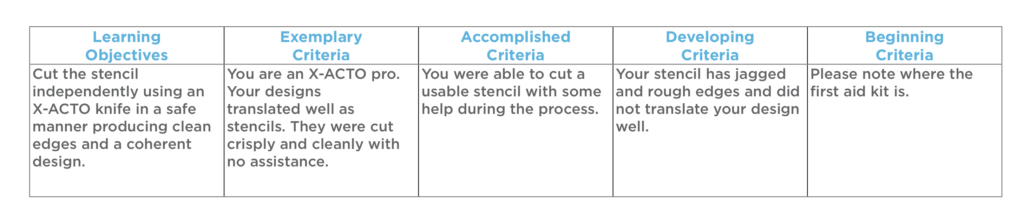

So, if you’re just trying to check off lists of actions, maybe you don’t need to create an entire rubric. Additionally, creating descriptors that only measure the frequency of accomplishment of a task can overly simplify things. If a student needs to achieve five points in a descriptor, does it matter which points are mastered? The example below shows how specific descriptors can differentiate a hierarchy of skills while also being checked off as a number of outcomes are being measured.

3. Be mindful of the language you use.

When creating rubrics, avoid subjective language. “Mostly,” ‘Excellent,” and “Somewhat” are all examples of terms that could be interpreted differently depending on the educator. In addition, make sure the descriptors make sense to students. A student should be able to use a rubric to figure out how they could improve next time.

Keeping these things in mind, I believe it’s ok to be a bit wordy in the rubric description. Using a descriptor like “Quality of line is rough and sketchy. Cleaner lines and attention to detail would improve the overall appearance of work” is much more helpful than “Line quality was poor.”

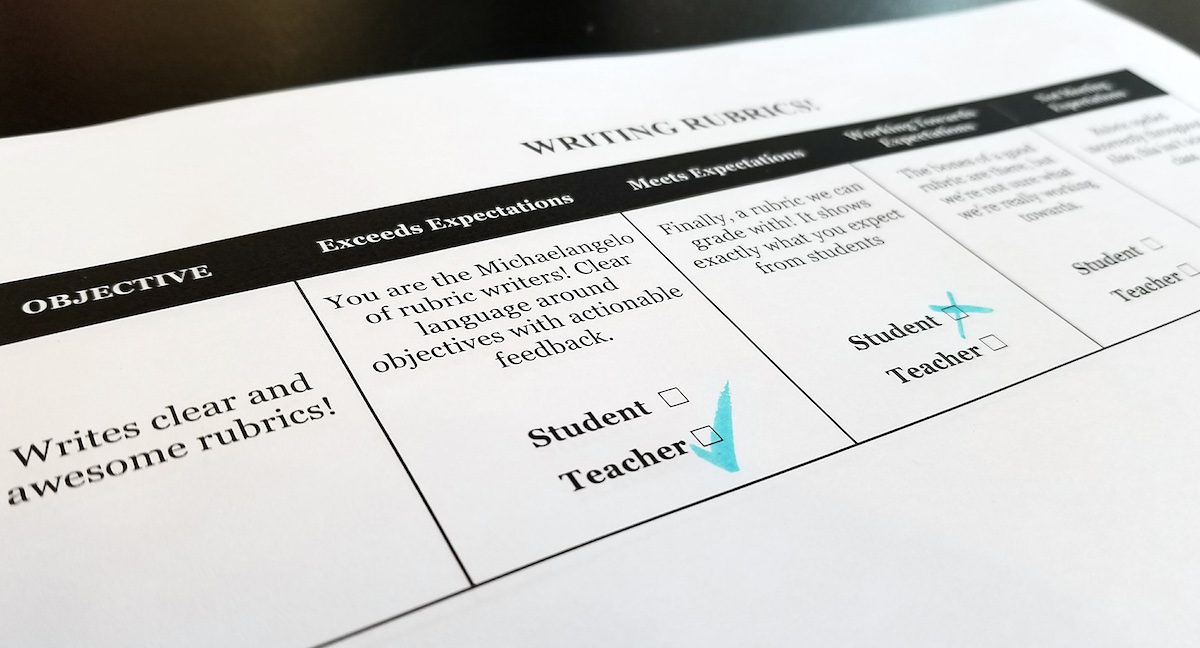

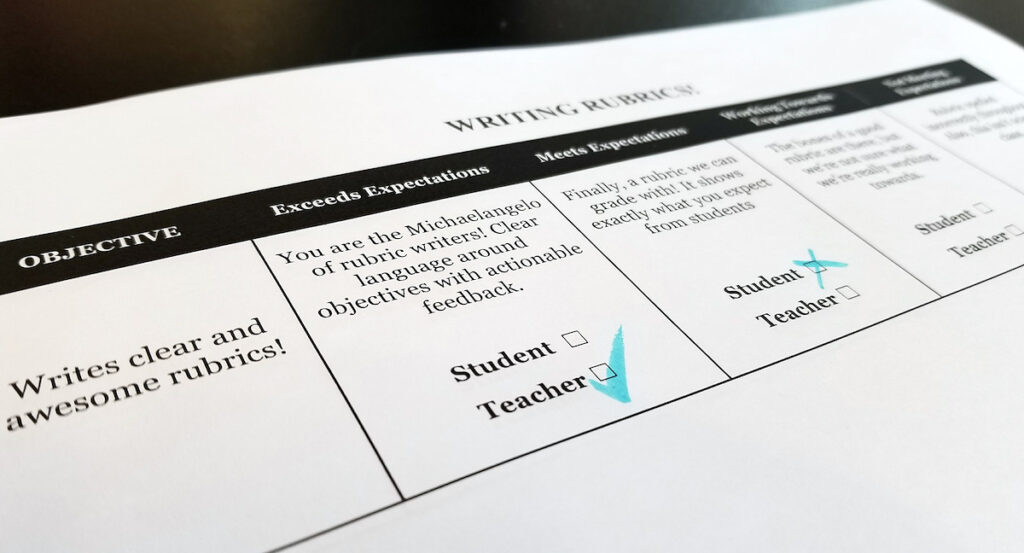

4. Now, find some space for humor!

I have yet to come across a student who expresses enthusiasm in reading through most rubrics and expectations. But I know I want them to give it their attention and understand what we’re trying to accomplish with the project. So, I try to give the descriptors a bit of personality. I’m not advocating you crack a joke in every box, but picking your spots while still giving some feedback makes a difference.

Choosing either the upper or lower extremes of descriptors will often be the most appropriate moments for levity. The ends of the scale lend themselves to hyperbole, and some humor brings the feedback into focus. In the example below, I am looking for technical proficiency with X-ACTO knives. Yes, students know to be careful with a sharp tool, but most of them don’t pay attention to appropriate cutting techniques. Cracking a joke here reminds them to take care, that there is, in fact, a first aid kit in the room, and that we don’t really want things to get gory in art class.

You need to do what works for you, but trying to keep things light in the descriptors helps to get students to read them. It might be that you bring some humor in when talking through the descriptors with your students. How you approach it matters, and it should always feel authentic. Don’t force the jokes.

Clear and engaging rubrics provide an important reflection tool for students. When we complete a project, the assessment provides information not just for teachers, but for students as well. It’s an important opportunity you don’t want to miss.

How do you review rubrics with your students?

Are there other creative and fun ways you engage students in assessment?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.