Have you heard these statements in your art room?

What should I pick?

What color should I use?

And everyone’s favorite: Am I done?

For all of these and all other questions like them, my answer is always the same: “What do you think?”

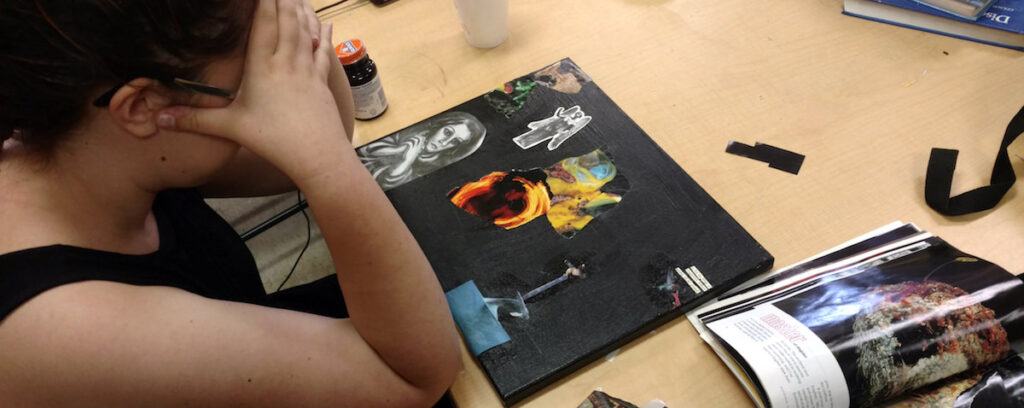

This question is challenging for many students. When I ask it for the first time, they struggle to answer. Often they try and feel out what they think I want to hear. This makes sense when you consider they are not actually concerned about making meaningful art, but rather making art to earn them an “A.” Generally in their past educational experiences, figuring out what the teacher wants is a better way to guarantee a good grade than developing their own opinions.

But even with rusty decision-making skills, kids can start to develop their opinions when teachers ask and truly listen.

It takes time and patience on the part of the teacher, but the results are worth it: students who are independently creative. Letting students struggle and learn from their own mistakes can feel uncomfortable for both the students and the teacher. However, it results in students feeling personal ownership of the art they create and leads to learning built on deep understanding. That’s why I let my students struggle, even when it’s hard.

Heather’s Story

Heather, a sophomore, had been working on her first oil painting for weeks. The closely cropped image of her dog was beautifully painted, with an expression begging the viewer to step through the canvas and play. As successful as this work in progress was, I had one worry: the background.

You see, Heather had spent weeks perfecting the dog’s face and the foreground. These areas were practically finished, but the white expanse of the background was still untouched. I asked what she planned to do there. She said she wanted to paint what was in the photo, which was a combination of small details and high contrast that looked time-consuming, challenging, and like it would take away from the rest of the image.

“Have you considered painting something else there?” I asked, hoping we could brainstorm together. No such luck.

A week later Heather spent a class period filling in the background.

The combination of too much contrast and hurried painting took away from the stunning foreground, just as I’d worried it would. She wanted to take it home that night, but I talked her into looking at it again the next day. “The background is just not working,” I told her and explained why.

She asked what I wanted her to do, her frustration palpable. We discussed options, including leaving it as it was, and then I left it up to her. I smiled as I saw her grudgingly start to extend the grass up to the top of the picture plane.

Teaching is not quick and it is not for the faint of heart. It would have saved me time and energy if I would have made her re-think the background earlier, but there would have been a cost – her ownership over her own work. When we use our expertise to make decisions for our students, we insert ourselves in their work. Instead, we have to let them struggle and gain the skills to decide their own paths. If we end up with artists who are dependent on us, then we haven’t done much real teaching.

What do you think? How do you handle it when students struggle? Is it good for them?

How do you help students deal with frustration?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.