There is no getting around it–the cannon of Western Art History is overwhelmingly male and white. That’s not to say we don’t respect and cherish it. The work represents a stunning array of beauty and power. In fact, the lack of diversity in the artists we know and love must be a product of the times in which they lived, right?

Wrong.

Over the course of history, there were women studying and working right alongside the great men of art history. Many overcame considerable barriers and achieved acclaim during their lifetimes only to be forgotten by later generations. Generations who attributed their work to their fathers or dismissed it outright because of their gender.

Here are three of their stories.

1. Edmonia Lewis

Lewis led a remarkable life spanning cultures and continents. Born to a black father and an Ojibwe mother in the mid-1800s, she was orphaned at a young age and spend most of her childhood raised by her mother’s tribe. At 15, she enrolled at Oberlin College, the first college in the US to admit students of all races and genders. Unfortunately, the town was not as liberal as the college, and Lewis was attacked by a mob and beaten after she was accused of poisoning her roommates. Although she was found not guilty in a subsequent trial, the incident ultimately contributed to her leaving without graduating.

She traveled to Boston, where she apprenticed with a sculptor, making busts of abolitionist heroes. The proceeds from sales of her work allowed her to travel to Rome, where she set up a studio and went to work creating powerful marble sculptures in the Neoclassical style. In Rome, she found a welcoming group of female expat American artists, attracted by the tolerance of the culture, proximity to great art, and accessibility of Carrara marble. During this time, Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha” was an incredibly popular poem and her series of sculptures illustrating it were highly successful, selling for large sums. In fact, she was so successful, she was able to bring what many consider her greatest work, “The Death of Cleopatra,” to the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia where it stole the show with its exquisitely draped fabric and original depiction of the great queen in the moment of her death.

The work didn’t sell and, possibly on account of its massive size, didn’t make it back to Rome. Lewis stored it for a time, but by 1892 there are reports of it being shown at a saloon, then, incredibly, as a grave marker for a horse owned by a gambler. Decades went by and Lewis was forgotten as Neoclassicism fell out of style. Cleopatra eventually was rescued from a storage room by a fire inspector, changing hands again and again before being acquired by the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, where she resides today.

For further reading see: “The Object at Hand” by Stephen May via smithsonianmag.org

2. Rose Valland

Valland’s contribution to art history is one of preservation rather than creation. Her story takes place during World War II. In the 1930s, Valland was a French art historian, teacher, and volunteer at the Louvre. During that time, the Nazis were looting the art collections of prominent Jewish families and storing the pieces in the Jeu de Paume museum. Valland was appointed to oversee the museum and spy on the Nazi operations. This was the perfect position for her because, unbeknownst to the German officers stationed around her, she not only was fluent in German but also had an excellent memory. Using her wit, she was able to keep remarkable records of the art that passed through under her watch.

Writes Sarah Wildman in The New Yorker, “Valland kept a careful log, night after night. Some of the ‘degenerate’ art, she wrote, was burned—including, it is believed, pieces by Dalí, Picasso, and Braques In 1944, as the war neared its end, Valland alerted members of the resistance to the last train bound for Germany carrying French art.”

As Valland recorded which of the Nazi elite came to the museum to shop for their personal art collections, she also kept track of when and where the art would be shipped and who the original owners were. Risking her life to collect this valuable information, Valland allowed the Resistance to avoid targeting trains carrying the cultural history of Europe.

After the war, Valland was commissioned in the French First Army and joined the Monuments Men. She used her records to track down the looted artwork that the Nazis had dispersed throughout Europe and began the process of restoring it to the rightful owners, which still continues to this day.

For further reading see: “Rose Valland ( 1898 – 1980 )” via monumentsmenfoundation.org

Artemisia Gentileschi

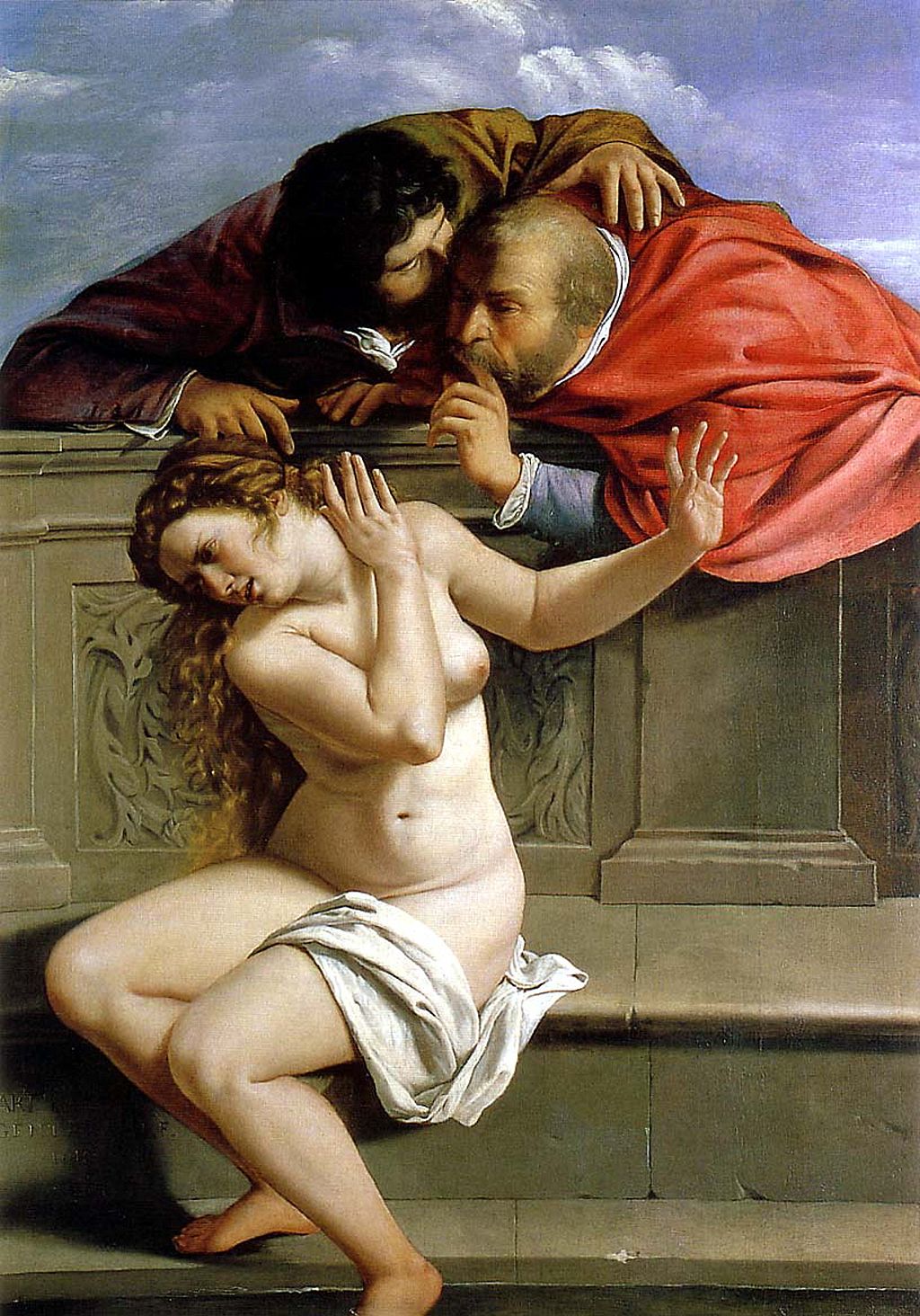

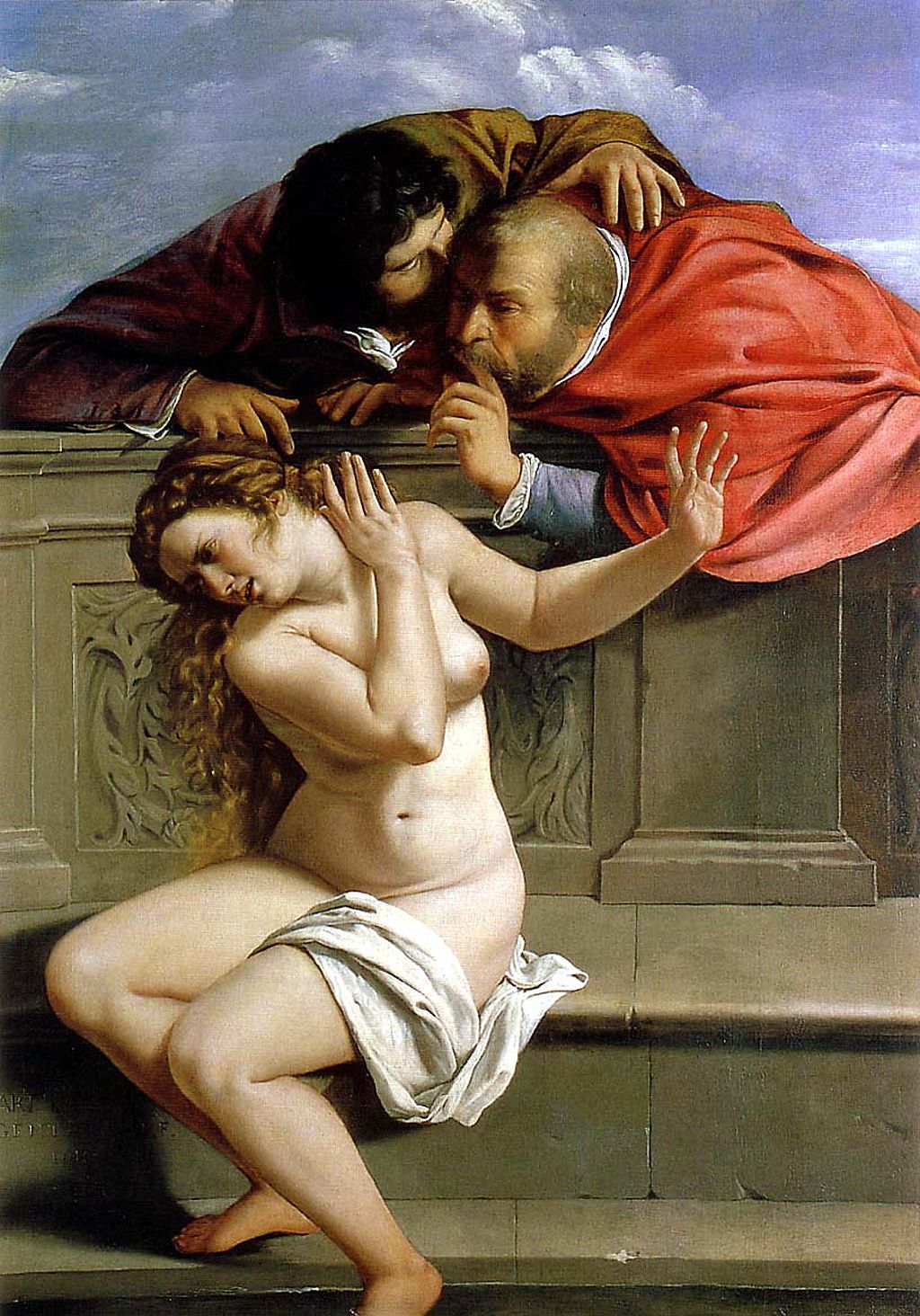

Gentileschi led a life as intense and as compelling as her artwork. She was born in Florence in 1593 and learned to paint from her father, the artist Orazio Gentileschi. Her work is stunning in its realism. At just 17 she painted a powerful interpretation of “Susanna and the Elders,” which shows a clear mastery of technique and expert storytelling. In this biblical painting, the figure of Susanna leans away from the lecherous elders who’ve propositioned her. Not only did this work reach way beyond the type of paintings women were traditionally limited to, it also showed Susanna disgusted and resisting instead of passive and coy as she was normally painted.

Often the power of Gentileschi’s work is overshadowed by personal trauma; as a teenager, she was raped by the colleague her father had hired to tutor her in painting. To reclaim his family’s honor, Orazio sued the man, Agostino Tassi, resulting in a trial that scandalized Rome. After the trial, Artemisia was quickly married and sent off to Florence. Through it all, Artemisia painted stunning work in the style of Caravaggio, with intense use of light and shadow and dramatic narratives. She even tackled some of the same subjects as Caravaggio, most notably the biblical story of Judith cutting off the head of the Assyrian general Holofernes to save her people.

Gentileschi was able to add something to her rendition of “Judith Slaying Holofernes“ that Caravaggio couldn’t– the perspective of a woman. While Caravaggio’s Judith appears to be holding her sword almost like a prop, Gentileschi’s Judith wields her weapon with power and intention, destroying her enemy. Gentileschi’s work was remarkable. So good, in fact, when she died after a successful career, later generations forgot about her, thinking work of that quality had to have been made by a man and attributing her painting to other followers of Caravaggio or her father well into the 1900s.

For further reading: “Long Seen As Victim, 17th Century Italian Painter Emerges As Feminist Icon” via npr.org

The contributions of these women to art history are profoundly based on their work alone, which is remarkable considering the barriers of sex and race they had to overcome. Theirs are just a few of the stories which fall outside of the typical list of important artists. They may be hard to find, but their stories are valuable and deserve to be remembered because Western Art has never belonged just to white men, our history books just make it seem that way.

Tell us, who is your favorite female artist?

Which female artists do you bring into your classroom?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.